Banner Photo by Ann Kramer

Featured Bird

Ruby-crowned Kinglet by Paul Jacyk/Macaulay Library

MEET THE RUBY-crowned KINGLET (Corthylio calendula) – by Jeff Sinker

If you have spotted a tiny, energetic, olive-green/gray songbird with two white wing-bars and a broken white eyering, chances are high that you are watching a Ruby-crowned Kinglet. One of North America’s tiniest songbirds, these kinglets move through the forest rather like the Energizer Bunny, rarely sitting still for more than a second or two.

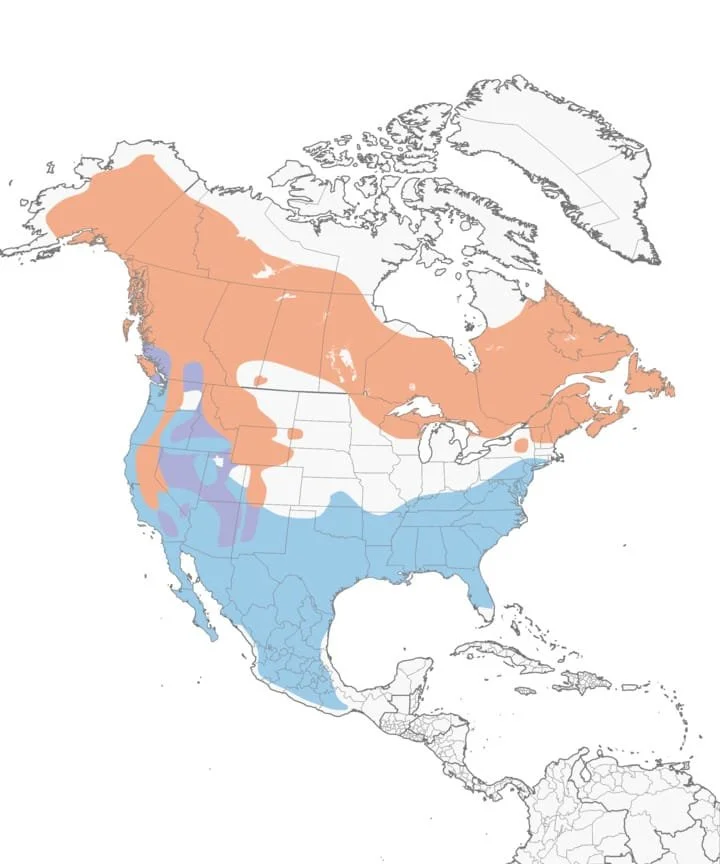

Both males and females are nearly identical in appearance, except the male has a red crown patch. However, this is usually concealed unless he becomes agitated or otherwise excited. Ruby-crowned Kinglets are habitat generalists during migration and non-breeding seasons. They can often be found foraging in the lower levels of trees and shrubs, sometimes even just a few feet off the ground. They have different habitat requirements during breeding season when they seek out old growth conifer and mixed forest habitats of the mountainous western US and Canada. Their diets include a wide variety of foods: spiders (and their eggs); many types of insects (and their eggs), plus berries, seeds and other plant matter. These kinglets breed farther north, and winter farther south, than the very similar Golden-crowned Kinglet.

Female Ruby-crowned Kinglets might be tiny in size, but they can lay a clutch of up to 12 eggs, which weigh nearly as much as she does! No other similar-sized North American passerine lays so many eggs. Both parents remain together until the young have fledged. Researchers find these kinglets difficult to study, on their breeding grounds, because of the remote location and the nests are usually about 100 feet above ground.

Ruby-crowned Kinglets can usually adapt to most human disturbance because of the wide variety of habitats they use, although logging in western forests could have an impact on local populations. Overall, their worldwide population is stable.

Learn more: www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruby-crowned_Kinglet

Photo credit: Ruby-crowned Kinglet by Paul Jacyk/Macaulay Library

Range map: www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Ruby-crowned_Kinglet

Purple: year-round; Blue: winter; Orange: breeding